Kabbalah and the Boundaries of Tradition

What This Essay Is Not About

A while back, I wrote about taking my sons to a Talne Rebbe yahrzeit, even though I have longstanding misgivings about the foundations of Hasidism and Kabbalah. This piece is not a sequel in the sense some readers might expect. I’m not going to rehearse the familiar arguments for and against the antiquity of the Zohar, nor litigate the evidentiary gaps in the transmission of Kabbalistic teaching. Readers are free to explore those debates and arrive at their own conclusions.

Transmission, Asymmetry, and Dismissal

For my purposes here, one point is enough: the transmission of the Talmud and Tanakh is historically traceable in a way that Kabbalah is not. That asymmetry matters.

It does not, however, settle the question I am interested in. The issue is not whether Kabbalah is convincing as a masorah, but what it means that it has become part of Judaism regardless. For some earlier Jewish philosophers and purists, the lack of a convincing transmission would have been sufficient grounds for dismissal.

I am not such a philosopher, and I am not a purist.

Canonization and Irreversibility

Whatever one thinks about its origins, Kabbalah has been canonized. For roughly five centuries it has informed halakhic rulings, liturgical language, and the conceptual vocabulary of Jewish thought. At this point, its influence is not confined to mystics or sectarians; it is woven into what many Jews experience as normative Judaism. Traditions do not require perfect origins to become permanent. Duration, use, and authority are sufficient.

Judaism as an Inherited Tradition

This leads to a second, more difficult point: Judaism is not a system we are free to redesign at will. It is an organic tradition, shaped by transmission, practice, and inheritance rather than by periodic acts of reconstruction. We do not stand outside it with editorial license. Our role is closer to that of stewards than architects. To imagine that inherited layers can be peeled away without reshaping what remains is to misunderstand the nature of continuity in a living tradition.

Influence, Purity, and Historical Reality

Accepting this position has implications that are easy to avoid but hard to escape. It requires acknowledging that elements of Jewish thought may have been shaped by external currents, historical accidents, or intellectual fashions of their time. This is often treated as a threat, as though influence were synonymous with illegitimacy. But traditions that endure do so precisely because they absorb, adapt, and reframe what they encounter. The alternative is a brittle notion of purity that collapses under historical scrutiny.

Paradox and the Talmudic Temperament

The paradox of this compromise is not lost on me. Like conservative arguments more generally, it conserves even the points at which conservation itself is said to have “failed.”

If this seems uncomfortable, it is worth remembering that the faith shaped by the Talmud was never built on tidy conclusions. It learned to live with paradox, to preserve dissenting voices, and to transmit unresolved arguments as faithfully as resolved ones.

The Cost of Revisionism

There is also a cost to revisionism that is too often ignored. Any serious attempt to reconstruct a Judaism without Kabbalah, or without its Lurianic forms, would not merely discard a disputed body of texts. It would sever contemporary Judaism from much of the spiritual vocabulary, conceptual depth, and religious insight developed by its most influential thinkers over the past five centuries. One does not remove Kabbalah without also losing access to the categories through which large portions of Jewish piety, law, and meaning have been articulated since.

The Rivash and a Third Path

In this, I find myself closer to the pragmatic restraint expressed by the Rivash in Responsum 157. He does not deny the existence of Kabbalistic wisdom, nor does he attempt to refute it. Instead, he acknowledges both its authority and its danger when severed from proper transmission. He reports that even his teacher, Rabbeinu Nissim, regarded Ramban as having gone too far in committing himself to Kabbalah. Lacking a direct transmission from a reliable master, the Rivash explains that he chose not to involve himself in that wisdom at all, noting how easily partial disclosures lead to error, revealing “a handbreadth while concealing many handbreadths.”

What is striking here is not skepticism, but discipline. The Rivash neither dismantles Kabbalah nor demands its removal from Judaism. He simply refuses to treat what he did not receive as binding upon himself. His response is neither credulity nor iconoclasm, but restraint.

This strikes me as the more honest posture. It acknowledges the authority Kabbalah has acquired without pretending that such authority requires universal assent or uncritical adoption. It also avoids the far greater distortion that would come from attempting to retroactively purify Judaism of influences that have already shaped its living form. Between naïve acceptance and revisionist erasure, the Rivash models a third path: fidelity without pretense.

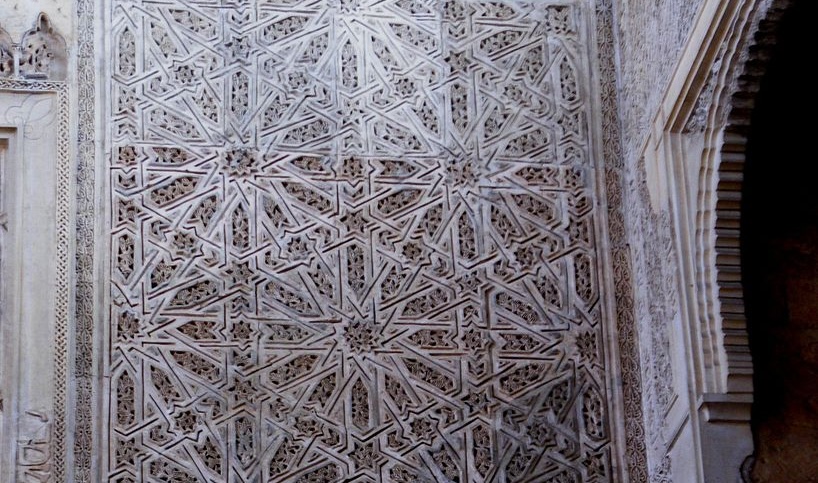

Featured image by Roy Lindman, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

The image was cropped for design considerations.