Hacking My Memory for Vocab

Most vocabulary doesn’t need tricks. If you review it in context, see it in sentences, and hear it in conversation, it eventually sticks. That’s the spacing effect at work (Ebbinghaus, 1885/1913; Cepeda et al., 2006). But every learner knows the stubborn few—the words you’ve looked up ten times and still forget. That’s when I switch to deliberate hacks. I use them in Anki and include them in spaced repetition.

And here’s the kicker: the act of inventing the mnemonic is as important as the cue itself. Psychologists call this the generation effect (Slamecka & Graf, 1978). When you make the association yourself, the effort of construction strengthens the memory more than just reading someone else’s idea.

My friend Dr. Franklin Zaromb PhD. pointed out that I neglected all the literature on retrieval and testing. He shared with me some recent research showing that this is probably the most effective mnemonic of all.

I’ve already covered how I use Anki Cards and how I use Lingualism cards for spaced repetition. I also run The Daily Derja, where I try to post a few times a week, partly to force myself to retrieve Derja. So I think I have this somewhat covered.

Still, it’s a significant omission from the memory literature I discussed—so I’m including this note here.

Examples: how I hack sticky words

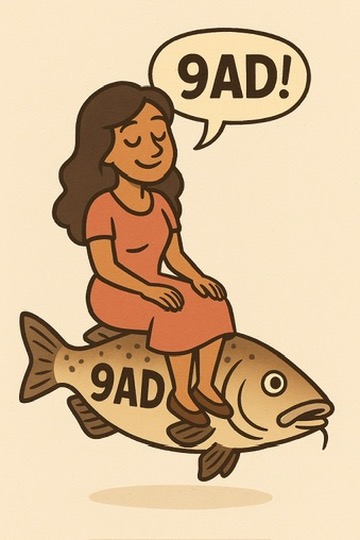

Here are three mnemonics I deliberately created for Tunisian Arabic words that wouldn’t stick—and that interfered with each other.

Why these three needed extra help (interference)

These forms tripped me up because they’re phonologically similar: 9ad, r9ad, l9a. The mnemonics are designed to pull them apart:

- 9ad (sit) ↔ cod (static, seated).

- r9ad (sleep) ↔ rakkad (dance) → absurd sleep-dance image.

- l9a (find) ↔ Q magnifier + clicker (explicit search + the final “click”).

Sometimes the best mnemonics come by accident

Not all mnemonics need to be carefully designed. Sometimes the best ones just happen.

A while back, while talking with my tutor Arij, she told me she’s often impatient and always shouting at her friends:

“Feesa! Feesa!” (Hurry up!)

That single anecdote stuck better than a thousand rote memorization drills. Now, whenever I hear the word فيسة (feesa), I don’t just see text on a card—I hear Arij’s voice in my head, yelling Feesa! Feesa! at her slow friend. 🤣

This is the power of a personal story: it links the word to a vivid, emotional, socially grounded memory. Because it came with humor, context, and a real person, it carved a deeper pathway than any flashcard could. Before that, I had forgotten the word many many times, now I can instantly recall it.

Why brute force fails

- Low salience: Some words don’t appear often enough in your input to build natural hooks.

- Interference: Similar-sounding words overwrite each other.

- Shallow processing: Just writing a translation drills form but not meaning.

When brute force fails, you need to deliberately give the brain a reason to keep the word.

What makes things memorable: attention & arousal

Memory isn’t neutral—it’s selective. The brain prioritizes what grabs attention and what carries emotional or biological weight.

- Von Restorff effect: distinctiveness makes outliers stand out (Hunt, 1995).

- Arousal strengthens memory: emotional stimuli are remembered more strongly (Kensinger, 2007).

- Visual salience: symmetry, movement, and exaggeration hijack attention (Itti & Koch, 2001).

This explains why mnemonics that are funny, shocking, vivid, or absurd work better than neutral ones. They force the brain to tag the word as “important.”

Why I often pick characters

Characters outperform abstract symbols for attention. There’s solid evidence that faces and bodies draw more attention than objects (Downing et al., 2004; Palermo & Rhodes, 2007), and that exaggerated features (caricatures) are especially sticky (Rhodes, Brennan, & Carey, 1987).

A specific attentional bias matters here too: eye-tracking shows men fixate quickly and longer on hourglass-shaped female figures (Singh, 1993; Dixson et al., 2011). Use that bias if it helps you remember.

Techniques I actually use

- Shock value – break a taboo, be jarring.

- Humor & absurdity – cartoonify the meaning; the sillier, the better.

- Sound-alikes – hijack familiar words (English/Hebrew/etc.).

- Personal references – tie the word to people or stories I already know.

- Characters – exploit attentional bias toward faces and bodies.

- Mini-stories – turn the word into a 1–2 panel comic.

The act of making is the memory

- Generation effect: creating your own associations boosts recall (Slamecka & Graf, 1978).

- Levels of processing: deeper, more elaborate encoding = stronger memory (Craik & Lockhart, 1972; Craik & Tulving, 1975).

- Dual coding: combining imagery + language strengthens recall (Paivio, 1990).

Even if the cue is crude or clumsy, constructing it yourself embeds the word deeper than repetition alone.

Iteration: keep or kill

Not every mnemonic lands. If I still blank on a word despite the cue, I replace it. The goal isn’t an Anki deck of dead jokes—it’s to tag the unstickiest words with a signal strong enough that forgetting them is harder than remembering.

Bottom line

For 90% of vocabulary, ordinary review plus exposure works. But for the 10% that resist, brute force fails. That’s when I hack the system. I load the word with humor, absurdity, or vivid characters, because those force attention. The effort of making the cue, plus the attentional tag, gives it a place in memory that plain repetition never will.

It’s a scalpel, not a hammer. And it works.

References (linked)

- Ebbinghaus, H. (1885/1913). Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology. English trans. (1913). Archive.org.

- Cepeda, N. J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J. T., & Rohrer, D. (2006). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks. Psychological Bulletin, 132(3), 354–380. PDF.

- Slamecka, N. J., & Graf, P. (1978). The generation effect. JEP: Human Learning & Memory, 4(6), 592–604. DOI.

- Hunt, R. R. (1995). The subtlety of distinctiveness: What von Restorff really did. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 2, 105–112. PDF.

- Kensinger, E. A. (2007). Negative emotion enhances memory accuracy. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(4), 213–218. DOI.

- Itti, L., & Koch, C. (2001). Computational modelling of visual attention. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2(3), 194–203. Nature • PDF.

- Downing, P. E., Bray, D., Rogers, J., & Childs, C. (2004). Bodies capture attention when nothing is expected. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance, 30(3), 488–507. PubMed.

- Palermo, R., & Rhodes, G. (2007). Are you always on my mind? Cognition, 104(1), 1–48. ScienceDirect.

- Rhodes, G., Brennan, S., & Carey, S. (1987). Identification and ratings of caricatures. Cognitive Psychology, 19(4), 473–497. PDF.

- Singh, D. (1993). Adaptive significance of female waist-to-hip ratio. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(2), 293–307. PDF.

- Dixson, B. J., Grimshaw, G. M., Linklater, W. L., & Dixson, A. F. (2011). Eye-tracking of men’s preferences for waist-to-hip ratio and breast size. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 43–50. PDF.

- Craik, F. I. M., & Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: A framework for memory research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11(6), 671–684. PDF.

- Craik, F. I. M., & Tulving, E. (1975). Depth of processing and the retention of words. JEP: General, 104, 268–294. PDF.

- Paivio, A. (1990). Mental Representations: A Dual Coding Approach. Oxford University Press. Google Books.